What's Truth Got To Do With It, by Joe Johnson

When I was public affairs counselor at the U.S. Mission in Panama, I learned of an impending visit by a very senior official to consult with the local government on the future of the Panama Canal – then under the control of the United States. I advocated announcing the visit and providing some press availability, but Washington wanted the visit under wraps. Fortunately, there were no rumors about the visit and no queries from local media. Considering the situation, I decided that on the day of that visit, the PAO would happen to be away on the golf course. The consultation came off with no publicity.

Was I right to avoid press contact on that day? Did I strike the right balance between confidentiality and disclosure?

I’m sure this is a familiar situation for today’s public affairs staffers, who grapple with other issues I never dreamt of: social media influencers, artificial intelligence and the atomization of news media. Where is the clear line between supporting a like-minded NGO and paying an influencer to parrot U.S. policies? When does an AI-created meme become deceptive?

Diplomats are part of a larger national security apparatus. Military and intelligence agencies conduct covert information and cultural programs from Washington and from locations abroad – some of which have damaged U.S. interests when made public. Public diplomacy’s job is to protect confidential information, but also to make sure that America’s reputational security is protected.

U.S. public diplomacy practice has undergone major changes over the past ten years. The emphasis has fallen on strategic planning and measuring effectiveness across information programs and cultural affairs – which are now properly understood as tactics promoting foreign policy.

I don’t hear much about ethical standards, though.

Communication ethics were embedded in the original design of American PD, which was separated from domestic political advocacy by the Smith-Mundt Act and was stamped in the first U.S. broadcast to Europe in 1942. "The news may be good. The news may be bad," the announcer intoned in that first broadcast, but "we shall tell you the truth." The U.S. Information Agency strayed into gray areas on occasion but essentially followed rules of factual communication, openly attributed, in its overseas programs and publications.

Fulbright scholarships were offered as merit-based competitions under clear selection standards, and professional exchange programs aimed to present a range of responsible opinion to foreign visitors. As international travel exploded over the past 60 years, American exchange offerings have also multiplied -- including the BridgeUSA private-sector exchanges – but have preserved fairness and insulation from domestic political agendas.

As far as I can see, the State Department’s public communications overall merit a high degree of trust and confidence, but some of those original norms seem to be eroding.

- The Voice of America claims truth-telling and balanced reporting in its Charter, protected by a “firewall” written into legislation to protect the “professional independence” of all U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM) journalists. Yet we have seen repeated challenges to reporting at the VOA and some of the USAGM “surrogate” media. Scrutiny is necessary, but not curtailment of editorial independence.

- The original Smith-Mundt ban on domestic dissemination of USIA materials became unenforceable with the advent of the internet. However, subsequent developments including the State Department’s merger of the International Information Programs and Public Affairs bureaus raise questions about the balance and range of opinions allowed in presenting U.S. policies to foreign audiences.

- For all State Department public diplomacy, longstanding traditions at USIA and State have been reinforced by a new body of PD doctrine, created painstakingly by the Under Secretary’s office and available online to all State Department practitioners. The doctrine is not made available to the public, though, and as far as I know it does not include an explicit, clear and simple set of guidelines.

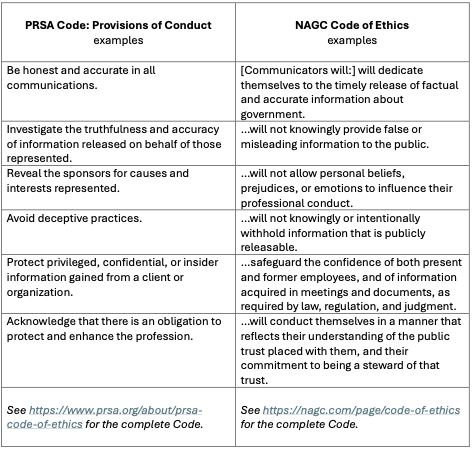

For our professional cousins in public relations, planning is also paramount, but ethics are up front. They are defined and published on line by the Public Relations Society of America and the National Association of Government Communicators. And it is not hard to map their standards to the practice of public diplomacy. The table shows a sample of the standards with the web location of each code of conduct.

For our professional cousins in public relations, planning is also paramount, but ethics are up front. They are defined and published on line by the Public Relations Society of America and the National Association of Government Communicators. And it is not hard to map their standards to the practice of public diplomacy. The table shows a sample of the standards with the web location of each code of conduct.Private-sector public relations people have always struggled with clients’ desires to bend the truth. The best of them hand in their resignations when they are asked to hide misconduct or to lie about their employer. They feel their personal standing with reporters, a core professional asset, will crumble if they’re caught in a lie.

Does public diplomacy need clear, published guidelines?

It’s not an idle question. The world is in a moment where the very notion of truth is challenged. Political leaders around the globe, not only in Russia and China, seek to hide facts and skew narratives to achieve their objectives. Russia, China and some other nations view their media and exchange programs as part and parcel of their influence operations. To paraphrase Tina Turner, “What’s truth got to do with it?”

Some politicians have tried to explain away the need to stick to verifiable facts. They argue that it’s o.k. to make up a story, repeat a falsehood, or launch an allegation without evidence if the goal is to raise public awareness or activate public sentiment.

And such behavior has real-world consequences. When digital media carry misinformation, become part of influence operations or swarm on sometimes insignificant events, they spread confusion and ignorance. That can make life-or-death differences in matters of public health, security, and even threaten government stability and public order.

The United States, led by its public diplomacy institutions, should be on the side of those striving for a healthier information environment. If there is an explicit code of conduct for United States public diplomacy practice, I would like to know about it. To state a commitment to fact-based communication and transparency would enhance our government’s reputation, enable us to call out the deceptive and abusive practices of adversaries, and provide clear guidance to public diplomacy personnel.

Our nation’s government will never kill all the bots and false websites, but it can at least set an example. Reliable, factual and open communication is a core element of American global leadership, and it should be a source of national pride.

Joe Johnson, a veteran public diplomacy officer, served until 2023 as an instructor in public diplomacy at the Foreign Service Institute. He is a member of the Public Relations Society of America, and held an Accreditation in Public Relations (APR.