POTUS and the VIPs, Part III, by Bill Wanlund

Here are three more stories by public diplomacy people who work with high-level official visits, at post or in Washington. As always, we are looking for YOUR story, which you can send to editor@PublicDiplomacy.org.

The Alpha and Beta, by Dan Whitman

In 1991, Spanish Prime Minister Felipe González went to Tel Aviv to meet with his Israeli counterpart, Yitzhak Shamir. Without prior notice, on October 24, they gave us at the U.S. Embassy in Madrid a good shock with their joint announcement that a Middle East Peace Conference would be held in Madrid (in - Madrid!) -- on six days’ notice. (“On the seventh, He rested” -- even God Himself might have taken more time for the planning process of such a meeting.)

October 24 was a Thursday, meaning President George H.W. Bush would be coming to Madrid the following Wednesday, along with Secretary of State James Baker III, and a few thousand of their closest friends. Speaking of God, the difference between Him and President Bush is that we’d seen President Bush and knew for sure that he existed.“Six days?” we said to one another at the Embassy. “Kidding, right?”Would this have been González’s way of making up for the Expulsion and Inquisition in one swoop? No one expected lots of good news coming out of the Middle East, but this would be the first time all the leaders would meet in the same room – Israeli, PLO, Arab states: this alone was to be a Big Deal.

October 24 was a Thursday, meaning President George H.W. Bush would be coming to Madrid the following Wednesday, along with Secretary of State James Baker III, and a few thousand of their closest friends. Speaking of God, the difference between Him and President Bush is that we’d seen President Bush and knew for sure that he existed.“Six days?” we said to one another at the Embassy. “Kidding, right?”Would this have been González’s way of making up for the Expulsion and Inquisition in one swoop? No one expected lots of good news coming out of the Middle East, but this would be the first time all the leaders would meet in the same room – Israeli, PLO, Arab states: this alone was to be a Big Deal.As a media factotum at the embassy, I can’t take credit for any of the gigantic logistical achievements that week. One of the most pressing challenges was to set up a filing center for the thousands of journalists who would be covering the event. Long before age of Wi-Fi, journalists filed their stories over phone lines, modems singing, “screek, scraawk, skriffle....” I am in awe of the technicians who managed to put in the seven thousand phone lines for media and White House staff. International press also received every supply they needed, because the U.S. and Spanish governments were on the line and needed the whole thing to work perfectly. In the end, their part of it did.

During those six days, a letter to the editor appeared in one of the Spanish dailies: “Yesterday I cried. I’ve been waiting six years for a phone line for my apartment, and this week they installed seven thousand overnight. When do I get mine?” Spain at the time hovered between sixteenth and twentieth century technologies: sometimes heavy ledger books in public utility offices with data entered by hand, sitting next to computer terminals in case anyone ever figured out how to use them.

At some point, the PM called the King Juan Carlos (the one who saved Spanish democracy on February 23, 1981, by standing off a military putsch). The King graciously said something like, “For Middle East peace? October 30 to November 1? Let me check…sure, go ahead and borrow the Royal Palace, I won’t be needing it those days.”

At some point, the PM called the King Juan Carlos (the one who saved Spanish democracy on February 23, 1981, by standing off a military putsch). The King graciously said something like, “For Middle East peace? October 30 to November 1? Let me check…sure, go ahead and borrow the Royal Palace, I won’t be needing it those days.”In the embassy, they had to organize driving pools, press briefing schedules, all sorts of protocol, and more. We in the media section were mainly on hold and understood we’d be needed at some point but weren’t calling any shots during the lead-up.

Prime Minister Shamir was a tough guy and had killed people during the struggle in the 1940s to establish and maintain a Jewish homeland in the Middle East. He was crafty and not a “nice guy” as Yitzhak Rabin later was, the poor guy who might have made a settlement with neighboring Arab states but was assassinated by a Jewish extremist November 4, 1995. We knew Shamir wouldn’t budge much in a public meeting like the one in Madrid, but hey, anything is possible, and why not give it every chance? Good on Shamir and González for trying. And of course both were in close touch with George H.W. Bush. The Spanish government hosted the conference, but the U.S. Embassy did most of the groundwork.

The role of the tuttofare (myself and others in the media section of the embassy) was to stand back, have no opinions, be ready for any damn thing that might happen. We knew we would be up nights doing nothing in particular and, chances were, preparing to be indispensable for a few seconds no one could foresee in the process. In most of these summits and international gatherings, you would spend 99 percent of the time just being alert, and perhaps one percent thinking up something that might resolve a problem.

My “station” turned out to be the meeting room itself, waiting at the far end just in case anyone important needed to grab me and get something happening. I got to know the sniffing dogs looking for possible explosives in journalists’ bulky packages with camera and recording equipment. In one case, the dog lost its focus entirely when it spotted a roast beef sandwich tucked in one of those bags. Everyone needed comic relief that day.

I wasn’t what they call “substantive,” but listened in to the proceedings, as each Middle East leader took the microphone to make his/her case (the PLO leader, Hanan Ashwari, a PhD in Comp Lit from the University of Virginia, was the only woman in the room). No American can fathom the subtlety and oblique references of a Middle Easterner, but it was clear no one wanted to be in that room. All had been dragged in by President Bush and especially by dragger-in-chief James Baker. One never said no to James Baker. They all knew Baker could make anyone’s God or Yahweh or Allah swoop down with swift punishment if he didn’t get his way: America’s best (and scariest) diplomat since Ben Franklin.

My moment came when a very stressed American came up to me and handed me a package. He was either U.S. media or maybe from WHCA, the White House Communications Agency. He was stressed. “Take this and deliver it to the motorcycle out on the street,” he said.

“Take this what, and where to?” I queried. I just wanted to get it straight.

“It’s pool tape. Will be on the air at 4:00.”

I wanted to know more, but he pushed me on my way.

I knew that “pool tape” was the Betamax-brand video cassette widely used for television broadcast. Nothing was digitized back then, so all depended on getting this physical object in the right hands. The “pool” was the very restricted number of journalists allowed in the room – sometimes by lottery – to record or observe for everyone, and they all took their turns either to be in the pool or to depend on what came out of it. Betamax – “Beta," for short -- was something like the Holy Grail, the key to the kingdom if you happened to come into possession of it. I knew there was fierce competition among the media for getting the scoop, but they were very collaborative in sharing primary sources. No one ever twisted or hogged the material, because they knew that karma would put them on the receiving end sooner or later in the process.

I looked back at the stressed official and gave a body gesture saying “?” but he just shooed me on and made it clear the need was immediate, with his hands saying, “Go, go now.”

I went out onto the street and sure enough, there was a network motorcycle with a driver waiting for the package. I think it was ABC. We made eye contact, and he swooped off with the Beta tape so it could be downloaded to a satellite feed for use by all the media within a couple of hours. This was close to having live coverage of a world event.

A moment later another came up to the curb. “Are you the guy with the tape?” the driver asked. “I am, yes.”

“Well, where is it?”

“I gave it to the guy on the motor…,” then I realized I’d handed the tape to the wrong motorcyclist.

I leave you a moment to ponder that. The stressed guy in the Palace had never said which media motorcycle should get the tape, so reasonably enough I handed it off to the first one who asked.

The second motorcyclist was very annoyed but buzzed off to God-knows-where, and of course I never saw him again.

World history will never take note of this contretemps, and in fact it didn’t matter much since pool media were very good at sharing their material with the others.

This was at the beginning of the second day of the three-day conference. The whole thing began to unravel, as the Syrian delegation said to someone, “This is a drag and a waste of our time, and we’re outta here.” Or words to that effect.

Baker and Bush weren’t having it. Arrangements were made with Bush’s close friend Prince Bandar, the Saudi ambassador to Washington who stayed many years and was Bush’s go-to person for Middle East dilemmas. If you come with me some day to the Spanish Royal Palace in Madrid, I can show you the exact spot where Prince Bandar handed an envelope to the Syrian delegation to convince them to stay for the three days. The legend was that twenty thousand dollars among friends was all it took to make the right thing happen.

And did I mention? No Middle East leader wanted to be at that conference, but none dared be seen as harming it or doing any sort of sabotage. I remember their sour faces and eyes darting toward the exits. They were basically prisoners for three days.

Shamir managed to find his way out. On Friday morning he announced to all, “I’m sure you are all familiar with Jewish practice, which forbids me to travel on the sabbath. As I must be in Tel Aviv for the weekend, I know you understand that I must be home before the sun sets this very day. Goodbye, best wishes, arrivederci.” Or, again, words to that effect.

Everyone in the room was stunned, betrayed, checkmated. The other delegates, all Muslims, might have resorted to the same ploy the day before, but now it was too late. President Bush was gone, but James Baker glared at everyone, daring anyone to make a move or comment. All stayed, minus the Israeli Prime Minister, the only one with a legitimate excuse to leave.

So it went with the Madrid Peace Conference, October 30-November 1, 1991. Still, it didn’t hurt that a precedent had been set for having all the parties in one room. This paved the way for the Oslo talks two years later, which gave some hope but also fizzled in the end. Madrid gave it a very good try, and the main achievement was the installation of 7000 phone lines in a city with antiquated infrastructure. For those technicians, the Whitman Prize for unprecedented progress toward World Peace.

(Photos: President George H. W. Bush with James Baker at a Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe; George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum; Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez, Spanish National Archives)

* * *

Bubba Mounts the World Stage

The Office of the State Department Historian wrote, “Upon his inauguration in January 1993, President Bill Clinton became the first president since Franklin Roosevelt who did not need a strategy for the Cold War—and the first since William Howard Taft who did not need a policy for the Soviet Union. … Clinton intended to leave the day-to-day management of foreign policy—including dealing with the “ancient hatreds and new plagues” of the former Soviet sphere of influence—to senior members of his national security team…. Clinton wanted to demonstrate his personal commitment to Russia in the emerging post-Cold War world."Such calculations were soon overtaken by events, however, as the challenges of managing relations between two former adversaries proved too much for his subordinates to handle on their own.” So, former Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott later recalled, “By the spring of his first year in office, Clinton had become the U.S. government’s principal Russia hand, and so he remained for the duration of his presidency.”

Clinton and Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first post-Soviet president, became friends; for the seven years the two were in office, they would meet 18 times. But there’s a first time for everything, as they say, and for “Bill and Boris” their initial personal encounter was in April 1993 at a summit in Vancouver, B.C. Unlike some administrations, Clinton’s White House was keenly aware of the important role that host country media play in amplifying the local impact of a Presidential visit. PDCA’s Joe Johnson was pressed into service to help prepare Clinton for that first meeting.

Present at the Beginning, by Joe Johnson

To those of us working at embassies, Presidential visits passed in a brief flash after long, tedious, and painful days rehearsing every move with a White House advance team. For President Clinton’s first foreign trip, to a summit meeting with Russian President Boris Yeltsin, I was selected to represent the U.S. Information Agency at the White House Office of Scheduling and Advance during the planning phase.

To those of us working at embassies, Presidential visits passed in a brief flash after long, tedious, and painful days rehearsing every move with a White House advance team. For President Clinton’s first foreign trip, to a summit meeting with Russian President Boris Yeltsin, I was selected to represent the U.S. Information Agency at the White House Office of Scheduling and Advance during the planning phase.A unique characteristic brought me this “honor”: I was available, unassigned at the moment.

Clinton’s transition team at the State Department had unceremoniously curtailed a U.S. Information Agency “coordinator” -- an office set up by the Bush Administration, which I supported as the staff aide to Stanley Zuckerman. When European Director Leonard Baldyga and his deputy, Brian Carlson, sent me to the West Wing I suppose they figured they could risk another ouster. I did complete this new liaison assignment; it lasted a whole ten days.

I worked for Anne Edwards, who headed Press Advance. Her job was to plan media access to the President’s events. Press Advance worked up the schedule for “accompanying press” – those reporters who followed the President throughout their travel – and to ensure their care and feeding, for which their organizations were paying dearly. Those not in the accompanying press contingent were out of sight, out of mind. A USIA priority was to maximize access for local press. Because the White House viewed USIA as a key partner and made heavy use of USIA personnel on the ground, we had some influence.

Having served at other POTUS visits, I knew the centrality of Press Advance for all media operations, so I tried to take full advantage of my access to them at the Old Executive Office Building. I held frequent meetings with Anne Edwards … by following her onto the porch whenever she took a smoke break. Plus, of course, group meetings and access to draft press schedules.

Through a lot of work on the phone and some shuttling between the OEOB and the Agency, and “a little help from my friends” at USIA, we garnered fair treatment for all the press at both summits. Press Advance and the White House Press Office paid extra attention to media on this first ride, and the new U.S. President projected an open, confident image to the world.

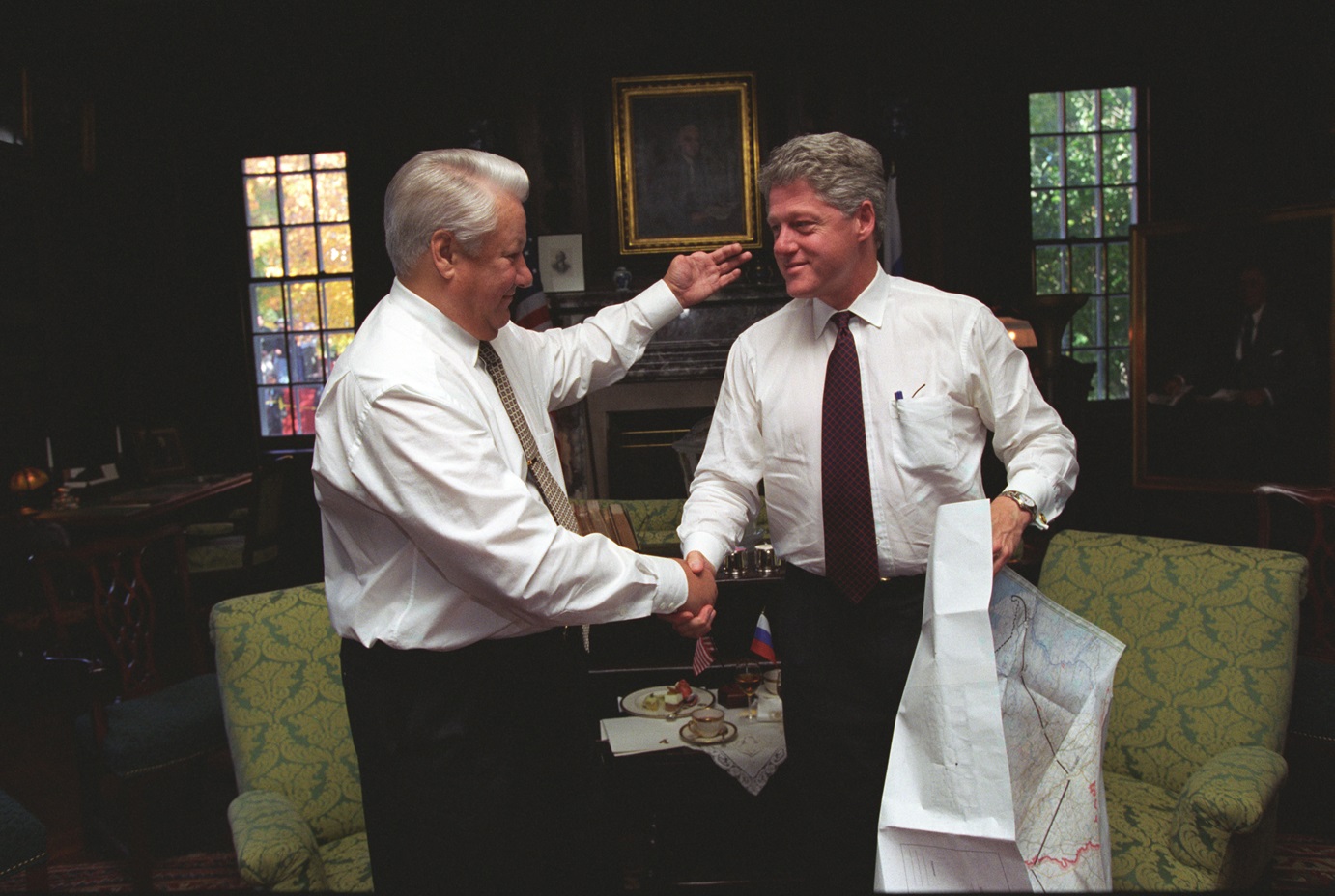

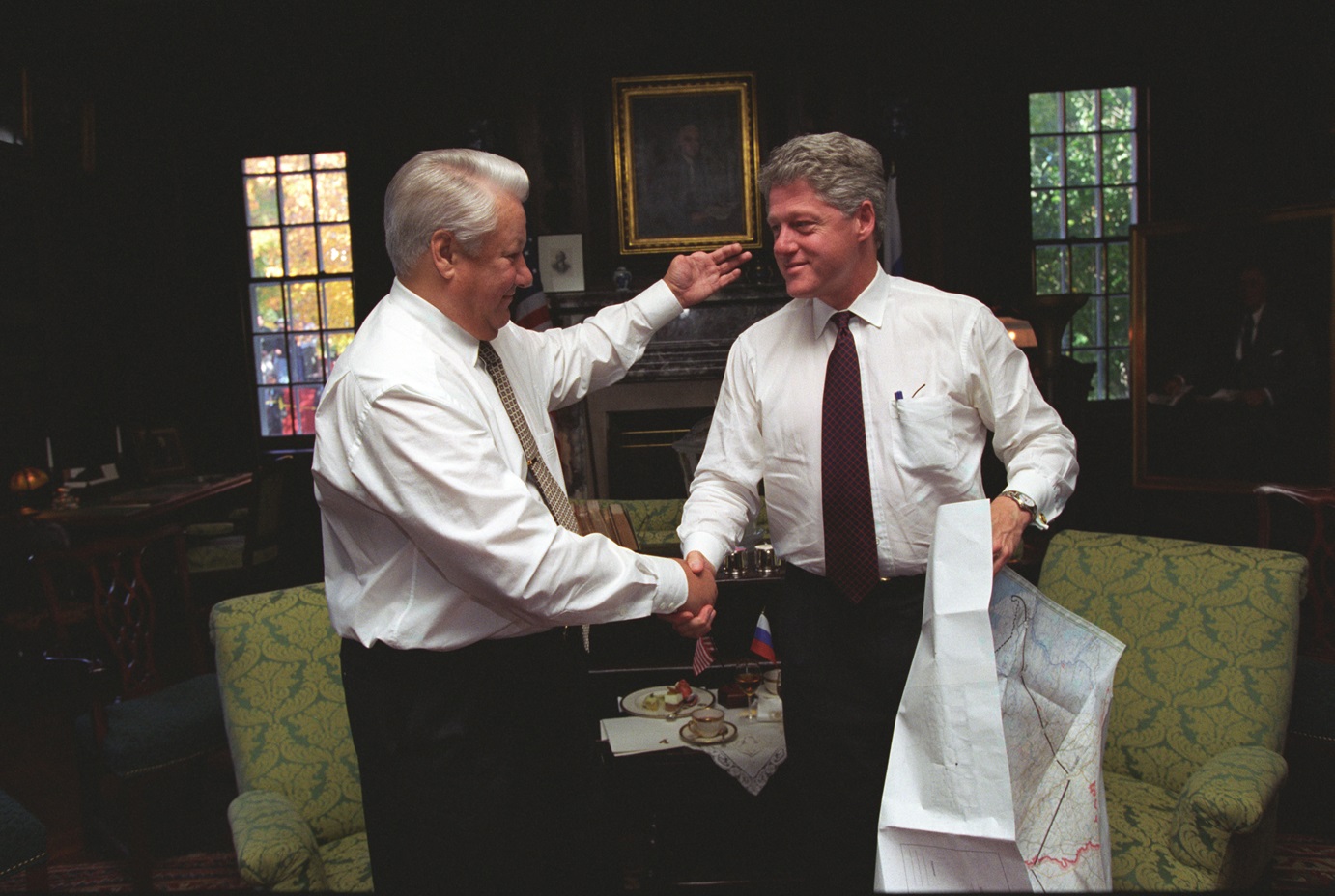

(Photo: President Clinton greets President Yeltsin of Russia at the Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, NY. White House Press Office, William J. Clinton Presidential Library)

* * *

PDCA Update editor Michael Korff was summoned to work on a subsequent high-level event attended by President Clinton, the 1996 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation [APEC] meeting in The Philippines. The Philippine International Convention Center in Metro Manila was the site of the Ministerial meetings. The AP archive video of the opening event briefly shows Clinton instructing his 17 fellow heads of state in “The Wave,” seen consummated about a minute into the clip. [Clinton’s reaction to the effort vary: Some observers believe he declared, “nice job”; others maintain he asked, “What was that!?” Judge for yourself.]

Visit of Bill Clinton to the APEC Meeting in The Philippines, by Michael Korff

The Philippines hosted the APEC Ministerial in 1996, and Bill Clinton and lots of people, including [then Secretary of State] Madeleine Albright, came. We had to staff all the meetings that the administration was going to have. We had countdown meetings with the Secret Service and the Advance Team every morning at 8:00. As I'm sure is true with all Advances, the White House people were almost all under 30 and enjoyed telling experienced officers how to do their jobs. One of the countdowns led to a spectacular public confrontation between the Embassy’s Regional Security Officer and the Secret Service advance. We all sat there dumbfounded as the confrontation unfolded, and I have no idea if the shouting match impacted the RSO’s career.

The Philippines hosted the APEC Ministerial in 1996, and Bill Clinton and lots of people, including [then Secretary of State] Madeleine Albright, came. We had to staff all the meetings that the administration was going to have. We had countdown meetings with the Secret Service and the Advance Team every morning at 8:00. As I'm sure is true with all Advances, the White House people were almost all under 30 and enjoyed telling experienced officers how to do their jobs. One of the countdowns led to a spectacular public confrontation between the Embassy’s Regional Security Officer and the Secret Service advance. We all sat there dumbfounded as the confrontation unfolded, and I have no idea if the shouting match impacted the RSO’s career.Although I was the Cultural Affairs Officer, I was the press control officer for the bilateral meeting of President Clinton with President Fidel Ramos of the Philippines. Traffic was paralyzed during the Ministerial, so the bilateral wasn't held in the President's palace in Malacañang but, rather, closer to where all the APEC events were taking place. My wife, who was working as a Consular Officer, ended up being U.S. Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky's control officer. At any other time, her control would have been a counselor of embassy for this or that, but because we were stretched so thin by this huge event, and there were so many people coming for it, they ended up turning to my wife to be Barshefsky's control officer.

Traditionally, on the last day of APEC, there is an event, supposedly off the record, where the delegates entertain one another. For the Manila ministerial, the event was at the Manila Hotel where the President was staying and where Douglas MacArthur had lived after the war. [In 1942, following Japanese troop advances, MacArthur had left, promising Filipinos “I shall return,” which he did in 1944. Later he became a sort-of regent as they were returning to democracy.] So that was where we had our press center. Next question: Who's going to run the press center? Answer: The CAO, of course! And I was told, "Since traffic is going to be a mess, you have to stay at the Manila Hotel" that night. So here I am, staying at the Manila Hotel, with almost no one in the press center on the evening of the entertainment, but I wasn't allowed to go to watch it.

Madeleine Albright did a soft shoe act with the Russian Foreign Minister: it was quite something. Supposedly the entertainment is off the record, but people smuggle out video of it. It was quite entertaining.

Clinton, to his credit, came to the embassy to greet the staff. Some presidents don't do that anymore, but it was nice that he did. I had been close enough to him at the bilateral, so I didn't need to be up close at the embassy, but my wife got to go up and shake his hand.

(Photo: Official APEC Photo of 1996 Ministerial; the representatives wore traditional Barong Tagalog shirts)

Bill Wanlund is a PDCA Board Member, retired Foreign Service Officer, and freelance writer in the Washington, DC area. His occasional column, Worth Noting, appears in the PDCA Weekly Update and addresses topics hopefully of interest to PDCA members.