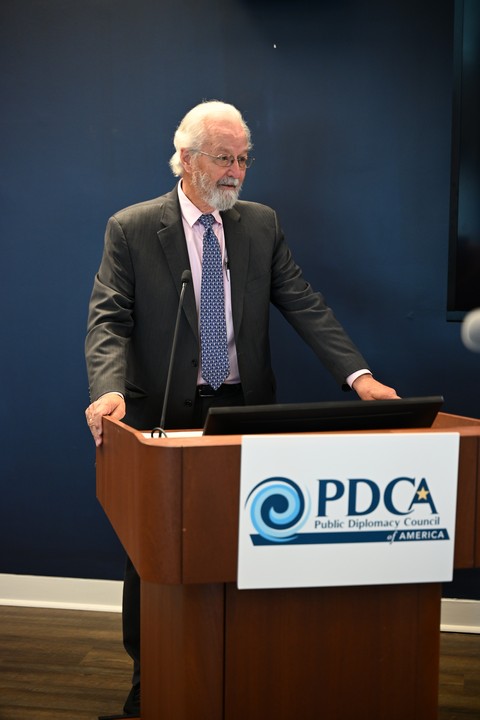

Eisenhower's Atoms for Peace initiative in the larger context of Eisenhower and Public Diplomacy, by Rick Ruth

I would like to begin by thanking our host today, Adam Powell, for inviting me to speak. He is unlikely to have known that Dwight Eisenhower is one of my personal heroes. I have had the privilege of spending several days at the Eisenhower Farm in Gettysburg and having discussions with Susan Eisenhower.

I would like to begin by thanking our host today, Adam Powell, for inviting me to speak. He is unlikely to have known that Dwight Eisenhower is one of my personal heroes. I have had the privilege of spending several days at the Eisenhower Farm in Gettysburg and having discussions with Susan Eisenhower.I would like to use my time to put Eisenhower's Atoms for Peace initiative in the larger context of Eisenhower and Public Diplomacy. Eisenhower was a master of public diplomacy, even though the term -- as we understand it today -- was not coined until 1965.

His entire presidency was a master class in public diplomacy. I think this is because Eisenhower embodied two traits:

First, he believed that exchanges, international engagement, citizen diplomacy -- instruments of peace -- arise out of their opposite -- violence, conflict, and injustice. Or more specifically, they arise out of the efforts of men and women of good will -- tough-minded men and women of good will -- to do something to reduce the likelihood of future violence and injustice.

Second, he believed that international engagement was part of the American character, that it’s in our DNA, not something the government imposes on us, like taxes or zoning.

Many in this knowledgeable audience will know, for example, that AFS and IIE are each over 100 years old, coming into existence long before Uncle Sam got into the game. Two of the founders of IIE, Nicholas Murray Bulter and Elihu Root, each individually received the Nobel Prize for Peace.

The most elegant definition of public diplomacy that I have encountered came -- not surprisingly perhaps -- from the pen of Thomas Jefferson when he wrote in the Declaration of Independence (a public diplomacy document if there ever was one) that we owe “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind.”

We have a story to tell, an experience to share, values we believe in and that we think matter to the world, and thus we have in us the wish to engage the world.

We may not see the like of Dwight David Eisenhower again -- growing up in Kansas and becoming the face of the 20th century. He was Supreme Allied Commander in Europe in World War II, Supreme Commander of NATO, and twice President of the United States. He even had time to slip in several years as President of Columbia University.

He was horrified by the carnage of WWII. His experience was not only to witness death and destruction firsthand, but also to shoulder the grave responsibility of sending young men into battle to kill and to be killed. I would think that the last previous president with that experience would have been General Ulysses Grant and, before that, General George Washington.

Eisenhower also witnessed the horror of Nazi death camps. He ordered extensive photographic documentation and, in one case, ordered nearby German villagers to assist with the burial of corpses so that they could not ever deny what had happened.

Then, with the power of the presidency he undertook three actions in the realm of public diplomacy that I would like to highlight today.

First, the Atoms for Peace initiative. I won't repeat what you have already heard, other than to say that it was masterful Public Diplomacy. It had everything -- diplomacy, public diplomacy, public relations, public affairs, national security, foreign policy, balance of power politics, marketing, branding, spin, psychological operations, and strategic communications. It addressed a domestic audience and a global audience; it addressed the present generation and future generations.

Adam's USC colleague Nick Cull -- the master chronicler of American public diplomacy -- called it, with no intent of disrespect -- a “splendid piece of political theater.”

Second, Eisenhower pulled together various operations, civilian and military, including notably the Voice of America, and established the United States Information Agency -- thus formally putting the United States in the forefront of the modern global struggle for hearts and minds.

Through all this, Eisenhower did not forget the importance, the centrality of human authenticity, of exchanges.

He convened a remarkable conference in 1956 -- in fact, on 9/11 of that year -- in the nearby Red Cross building and launched what he called the People-to-People program.

He invited the director of the Philadelphia Philharmonic but also the head of General Mills, a director of the National Gallery of Art but also the CEO of American Express, he invited the cartoonist Al Capp (some of you here will remember him), and also the president of the AFL-CIO and the head of the American Legion and the NY Boxing Commissioner. One invitee was shown on the White House invitation list simply as "Faulker, William - writer."

You get the idea.

President Eisenhower told the assembled "the purpose of this meeting is the most worthwhile purpose there is in the world today: to help build the road to peace, to help build the road to an enduring peace."

I suspect we would all agree today that this is still what we are about.

And the specific questions the President posed are today’s questions --questions that many of you grapple with every day:

- How do we dispel ignorance?

- How do we present our own case?

- How do we strengthen friendships?

- How do we learn of others?

Thank you.

(Top photo courtesy of Bruce Guthrie, taken at PDCA's December 8, 2025, forum on President Eisenhower's Atoms for Peace speech at the UN General Assembly)

In a career spanning more than four decades with the United States Information Agency and the Department of State, Rick Ruth was recognized as an accomplished global diplomat, an experienced manager, sought-after public speaker, and skilled troubleshooter. An inclusive team-builder, Rick brings calm leadership to crises and unsettled situations.

In a career spanning more than four decades with the United States Information Agency and the Department of State, Rick Ruth was recognized as an accomplished global diplomat, an experienced manager, sought-after public speaker, and skilled troubleshooter. An inclusive team-builder, Rick brings calm leadership to crises and unsettled situations. Rick served as a Foreign Service Officer (Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Soviet Union) and as a member of the Senior Executive Service. Prior to joining the Foreign Service, he taught Russian language and literature at the University of Arizona. He joined the government in the mid-1970s as a Russian-speaking staff member on a traveling U.S. cultural exhibition in the Soviet Union.

Rick served as deputy chief of staff to the last four directors of the United States Information Agency (1988 to 1999) and with the integration of USIA and the Department of State, he organized the office of the Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs and served as its first chief of staff.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Rick was the sole public diplomacy representative on the senior-level steering committee responsible for coordinating the U.S. State Department's response to the attack. In response to the 9/11 attack, he originated the first high school exchange program for the Arab and Muslim world (now known as the Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Study Program), thus far engaging 13,000+ young men and women from more than 45 countries.