What’s in a name? A historical footnote on Senator Fulbright, the Kennedy Center and its Rebranding, and the Crisis of U.S. Public Diplomacy, by Lonnie Johnson

In 1976, Senator J. William Fulbright looked back on his career in a brief retrospect published in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. He observed that he considered his association with the Fulbright Program and its intention to promote “mutual understanding among the peoples of the world” through educational and cultural exchange as “the most significant and important activity I have been privileged to engage in during my years in the Senate.” Fulbright’s primary concern was the maintenance of peace in the nuclear age, and he considered the stakes of not doing so apocalyptic: “I believe that more and improved programs for exchange of persons and intellectual interchange around the world offer the best prospect for creating the understanding and rationality necessary to avoid annihilating ourselves in a burst of nuclear missilery.”

In 1976, Senator J. William Fulbright looked back on his career in a brief retrospect published in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. He observed that he considered his association with the Fulbright Program and its intention to promote “mutual understanding among the peoples of the world” through educational and cultural exchange as “the most significant and important activity I have been privileged to engage in during my years in the Senate.” Fulbright’s primary concern was the maintenance of peace in the nuclear age, and he considered the stakes of not doing so apocalyptic: “I believe that more and improved programs for exchange of persons and intellectual interchange around the world offer the best prospect for creating the understanding and rationality necessary to avoid annihilating ourselves in a burst of nuclear missilery.”The Fulbright Program, which the Department of State traditionally has heralded as the “U.S. government’s flagship international educational and cultural exchange program,” is indisputably Fulbright’s overarching claim to fame. The recent rebranding of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts as the “Trump-Kennedy Center” provides an occasion to look back on Senator Fulbright’s important but completely underexposed role in the original establishment and naming of the Kennedy Center and the questionable benefits of partisan political tinkering with historical monuments and national institutions, like the Kennedy Center and the Fulbright Program.

+ + + + + + + + +

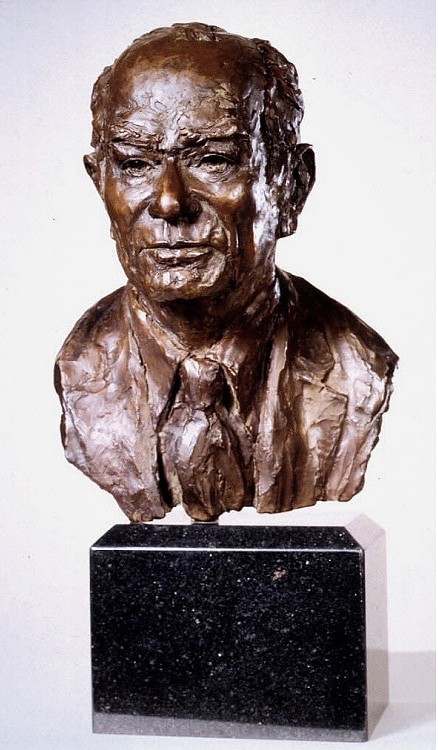

On March 13, 1990, the Associated Press ran a brief and instructive story on the placement of a bust of the former Senator at the Kennedy Center “to commemorate his little publicized role in the creation of the national performing arts center.” I shall return to this story after briefly outlining the history of the Kennedy Center as portrayed on its website, which curiously has nothing to say about the important roles Senator Fulbright played. (We will return to the noteworthy fact that the website sported a new “Trump Kennedy Center” header less than 24-hours after the Kennedy Center Board of Trustees voted to rename the institution “The Donald J. Trump and The John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts” on Thursday, December 19, 2025.)The history pages on Kennedy Center website reference four key events between 1955 and 1964:

- In 1955 President Eisenhower established an advisory committee on the establishment of a national cultural center in Washington, D.C., because the nation’s capital did not have a representative public venue to showcase America’s cultural achievements or to host world-renowned artists from other countries. There was no representative theater, opera house, or concert hall in Washington, D.C., that could remotely compete with the well-established venues that graced foreign capitals in abundance elsewhere: ranging from the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow in the East to the Royal Albert Hall in London in the West with scores of other larger and smaller prestigious national venues in between.

Little is to be found about this advisory committee or its work. However, the Eisenhower years were the first heyday of American cultural diplomacy – with jazz and sports being deployed as part of America’s popular cultural arsenal, too. President Eisenhower fully appreciated the role of culture and cultural diplomacy in the United States’ confrontation with the Soviet Union, and he recognized that the United States had some catching up to do in this competition for global attention which Joseph Nye later would describe as exercising “soft power.”

- On September 2, 1958, President Eisenhower signed the National Cultural Center Act (PL 85-874) into law, and Fulbright played an important role in this initiative, which goes unmentioned on the Kennedy Center website and to which we shall return. The Act established a Board of Trustees consisting of a representative mix from governmental departments and government-sponsored institutions, ex officio representatives from the Senate and the House of Representatives, and private citizens appointed as general trustees by the president of the United States.

Today the Board of Trustees is large and has 68 members: five First Ladies (Melania Trump, Jill Biden, Michelle Obama, Laura Bush, and Hillary Clinton) as Honorary Chairs; six officers (with President Trump as Chair, and Richard Grenell, as President); 34 members appointed by the President (which reads like a Who’s Who of his supporters); and ex officio members: nine from various governmental departments and institutions and seven members of the Senate and seven members of the House of Representatives designated by Congress on a bipartisan basis.

The National Cultural Center Act mandated the Board of Trustees to raise money to construct a national cultural center for the Smithsonian Institution “with funds raised by voluntary contributions,” and it also had a sunset clause that sufficient funds had to be found “within five years.”

- President Kennedy took a special interest in raising funds for the National Cultural Center, and in 1961 he appointed Roger L. Stevens its chairman. Stevens was a visionary, who oversaw the construction of the Center and provided legendary leadership for 30 years. JFK also appointed his wife, Jacqueline, and Mami, the wife of former president Eisenhower, as the honorary co-chairwomen in a funding campaign launched in November 1962. However, the Kennedy Center website does not report that fundraising lagged dramatically, which made it necessary for Kennedy to sign additional legislation providing for a three-year extension of the original legislation’s sunset clause in August 1963.

- Kennedy’s assassination three months later on November 23, 1963, put the completion of the National Cultural Center in a completely different context. Congress responded to the assassination of President Kennedy with a “Joint Resolution for renaming the National Cultural Center as the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, authorizing an appropriation therefor, and for other purposes” which enjoyed overwhelming bipartisan support and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law on January 23, 1964 (PL 88-260). Senator Fulbright (D-Arkansas), who started serving as the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1959, was responsible for introducing this joint resolution to the Senate on December 5, 1963, just thirteen days after Kennedy’s assassination. (This is another detail the Kennedy Center website fails to mention.)

- officially designated the National Cultural Center as the “John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts” and gave it the additional role of serving as a “living memorial” and “a suitable monument dedicated to the memory of this great leader”;

- provided a generous appropriation to kick-start the construction of the center in conjunction with private donations, thus establishing a public-private partnership as the operative model for the Center’s operation;

- designated the center as the “sole national memorial to the late John Fitzgerald Kennedy within the city of Washington and its environs”; and

- authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to accept gifts from abroad “contributed in honor of or in memory of the late President John F. Kennedy” to help complete this project. (Over 40 countries did so: with Carrara marble from Italy, silk wall coverings from Japan, crystal chandeliers from Austria and Sweden, etc., etc.)

Fulbright played two important roles in the establishment of the Kennedy Center. First, he was one of the missing links between President Eisenhower’s establishment of an advisory committee on the construction of a national cultural center in 1955 and the passage of the National Cultural Center Act in 1958 – a bipartisan effort – and second, he helped shepherd the entire project to fruition.

According to the AP story cited above – “Fulbright Bust placed at Kennedy Center" – the purpose of this placement of a bust of the former Senator at the Kennedy Center was “to commemorate his little publicized role in the creation of the national performing arts center” and Fulbright recalled that he accompanied the Soviet ambassador to a performance of the Bolshoi Ballet in a local movie theater in 1957. The theater was such a bad locale, he said, that he introduced legislation the next day authorizing a national cultural center in Washington. This anecdote is not documented elsewhere, but if it is true, it has an affinity to how Fulbright introduced the initial legislation for the Fulbright Program. It was snap decision he made more or less on his own.

Sherry Mueller, Distinguished Practitioner in Residence at American University’s School of International Service and former Co-President of the PDCA, has a somewhat different and more detailed version of the same story that Fulbright personally related to her. She met Senator Fulbright in the early 1980s when she was working at the Institute of International Education and responsible for organizing the first Fulbright Enrichment Seminar that brought 180 Fulbright graduate students from all over the world to a three-day seminar in Washington, D.C. The highlight of this event was a luncheon where Fulbright spoke and then interacted individually with many of the students. Her first encounter with the senator provided the basis for what was to become a long friendship with him and his second wife, Harriet Mayor, after they married in 1990.

At an event of the Fulbright Association in October 2019, Dr. Mueller shared some of her personal recollections on her association with Fulbright and reported that she “once asked Senator Fulbright what he considered his greatest accomplishment in addition to the Fulbright Program.” He responded by explaining

"how he was one of the only American leaders who would hang out with the Soviets when they were in Washington. Once he accompanied Foreign Minister Gromyko to a performance of the Bolshoi Ballet at Constitution Hall. He was embarrassed that the stage was too small and concluded that the Nation’s Capital needed a proper center for the performing arts. He and others worked to establish such a place, but it was only after President Kennedy was assassinated that they could muster the necessary support in Congress for the Center for the Performing Arts – by naming it after President Kennedy."

R.W. Apple, Jr., reinforced the importance Fulbright attached to his role in helping establish the Kennedy Center in his obituary “J. William Fulbright, Senate Giant, Is Dead at 1989” in The New York Times on February 10, 1995. After noting his many achievements, Apple observed: “Yet, Mr. Fulbright said in an interview six years ago that he was proudest of his role as legislative father of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.”

The AP story on the placement of a commemorative bust for Fulbright at the Kennedy Center in 1990 also provides some important insights into the second role Fulbright played in shepherding the Kennedy Center to completion:

After Congress approved the bill in 1958, Kennedy Center officials said, Fulbright ‘provided extraordinary energy and leadership’ during a turbulent period when questions of financial support, construction site, architectural design, and administration of the center were debated. Roger L. Stevens, founding chairman of the Kennedy Center who celebrated his 80th birthday Monday, said Fulbright’s role had never been fully recognized. ‘If it had not been for people like him, we would never have succeeded in making the Kennedy Center a reality,’ he said.

Fulbright’s introduction of the joint resolution renaming the National Cultural Center as the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts as a “living memorial in his honor” to the Senate on December 5, 1963, is just one example. It is also noteworthy that Edward Durell Stone, architect of the Kennedy Center, and Fulbright were lifelong friends, who grew up in Fayetteville, Arkansas together.

+ + + + + + + + +

After retiring from the Senate in 1974, Fulbright became a partner at Hogan & Hartson, one of the most prestigious Washington law firms at the time, and his partners commissioned a bronze bust of Fulbright to commemorate his achievements. Gretta Bader, a sculptress renowned for her portraits, crafted the bust that was gifted to the National Portrait Gallery in 1982. This bust – enhance by a small commemorative plaque – was put on permanent display at the Kennedy Center on March 13, 1990, and initially displayed outside of the box tier in the Kennedy Center’s Opera House lobby.Gretta Bader also sculpted a full-length statue of Fulbright that has become a landmark on the campus of the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. (She incidentally was married to William “Bill” Bader, who worked on Fulbright’s staff in the later 1960s and served as the first Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs from 1999 to 2001.) President Clinton dedicated this Fulbright statue at the University of Arkansas on October 21, 2002, in a ceremony that highlighted the 50th anniversary of the German-American Fulbright Educational Exchange Program. It stands in front of the main entrance to Old Main, the historical centerpiece of the University of Arkansas that housed the university’s College for Arts and Sciences that was renamed the Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences in his honor in 1988.

I recall seeing the Fulbright bust for the last time at the Kennedy Center at a visit somewhere around 2017, and then it was returned to the National Portrait Gallery. This is a good example of how institutional forgetfulness or amnesia works and more an example of benign neglect than anything else, I assume. However, it also is symptomatic for the kind of treatment the memory of J. William Fulbright and the history of the Fulbright Program have intentionally received from the State Department in the past decade. A few examples suffice to illustrate this point.

The gala celebration held at the Kennedy Center on November 30, 2021, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Fulbright Program would have been a wonderful opportunity to recall the roles Fulbright played in the establishment of this august institution, too. However, the State Department not only missed this opportunity; it expunged Fulbright from its version of the program’s historical record.

In the course of the carefully crafted remarks the State Department drafted for a highly orchestrated one-hour-and-forty-minute event that was livestreamed, the name of Senator J. William Fulbright was not mentioned once nor was an image of him shown. In the run-up to the Fulbright Program’s 75th anniversary, Fulbright – the author of the program’s foundational legislation in 1946 and its most important political patron – disappeared from the State Department’s rendition of its own history.

This Soviet-style erasure from the historical record coincided roughly with the illiberal global “peak” in wokeness that followed the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota, at the end of May 2020, and it was an act of retroactive retribution for Fulbright’s voting record against civil rights as an orthodox Southern Democrat in the 1950s and 1960s. His complex legacy and memory as an international educator, anti-Vietnam War dissident, and Southern Democrat had become “inappropriate.”

I appreciate having had an opportunity to talk about this astonishing revision of the State Department’s historical narrative at a PDCA First Monday Forum on October 2, 2023. (PDCA posted a video of my talk “Remembering Fulbright: The Senator, the Program and Public Diplomacy” on its YouTube channel, and a transcript thereof with footnotes and hyperlinks can be downloaded here.) As Karin Fischer observed at the time in The Chronicle of Higher Education, “The Fulbright Program is Quietly Burying its History.”

The record of the Trump administration with reference to Fulbright and the Fulbright Program also has been characterized by its efforts to eradicate all vestiges of what it considers to be “woke” public diplomacy from the Biden era: a pejorative term popularized in a report Simon Hankinson drafted for the Heritage Foundation that appeared in December 2022 and is cited in the forward to the Heritage Foundation’s 2025 Project.

After the election of Donald Trump in 2024, the Trump administration’s anti-diversity backlash had profound implications for the Fulbright Program. First, President Trump issued a series of executive orders on or after January 20, 2025, conceived to address “radical and wasteful government DEI programs and preferencing,” “gender ideology,” and “illegal discrimination.” Second, on February 3, 2025, Acting Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy Darren Beattie informed the Bureau for Educational and Cultural Affairs and the members of the twelve-person J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board (FFSB) responsible for the oversight of the program and final approval of all of its participants – all presidential appointees made by President Biden – that he intended to review all Fulbright awards to ascertain if they were in “alignment” with the Trump administration’s policies.

Third, on March 4, 2025, Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a cable providing “guidance” on the new procedures U.S. embassies and binational Fulbright commissions should follow for the selection of Fulbright grantees “for the 2025-2026 academic year and beyond.” Its key passage read: “Candidate projects/research proposals recommended for selection under the program must be in alignment with both the specific requirements and the spirit of the Executive Orders on DEIA and Gender Ideology; as well as any other Executive Orders that may be relevant to a specific project area.”

The PDCA Newsletter posted a longer and finer grained analysis of mine on the complex of problems associated with these measures and the current state of the Fulbright Program in its November 23, 2025, issue: “Observations on the Fulbright board resignations in the Netherlands and the state of the Fulbright Program.” Let it suffice here to mention three points associated with the “Fulbright problem” and to relate them to what perhaps can best be called “the Kennedy Center problem.”

This past spring, the Trump administration violated federal statute, over seventy-five years of established administrative practice, and 49 bilateral international agreements with countries that have established binational Fulbright Commissions by (a) abandoning grantee selection procedures based on non-partisan subject matter expertise and the collaborative binational selection of grantees and (b) unilaterally dictating that the State Department alone will ultimately determine which grantees fulfill its politically partisan criteria.

Using undisclosed criteria and undisclosed methodologies, an undisclosed number of people at the State Department covertly reviewed and then revoked an undisclosed number of Fulbright awards from the 2025-26 program cycle – hundreds and hundreds according to available sources – in April and May 2025. Furthermore, the State Department has all of these procedures in place to ideologically – and clandestinely – vet and eliminate grant applications for the current program cycle for 2026-27 that is in full swing.

+ + + + + + + + +

In conclusion: If one compares the older “Fulbright Program problem” with the recent “Kennedy Center problem” there are some striking similarities.Both are based on obvious and unprecedented violations of federal statute and dramatic departures from decades and decades of administrative precedent. There is nothing in the current statutory framework for the Fulbright Program – the Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act of 1961, better known as the Fulbright-Hays Act – that the State Department could use to even remotely justify its interference in the Fulbright Program’s grantee selection process, and there also is nothing in the pertinent federal legislation for the Kennedy Center – the original 1958 legislation or the 1964 joint resolution – that the Kennedy Center’s Board of Trustees could use to justify its decision to change the name of the Kennedy Center to include President Trump’s name. As the Washington Post reported on December 19, Kennedy family members and Democratic leaders immediately condemned the change, and legal experts opine that only Congress can change the center’s official name.

Educational and cultural exchange and cultural diplomacy work best and are most credible if they are non-partisan or at least bipartisan, and there always have been programs and institutions that have been considered part of a non-partisan national heritage that has weathered the ebb and flow of partisan politics well over the years. The Fulbright Program, the Kennedy Center, the Smithsonian, and many other federal programs and public institutions are composite parts of an American national heritage, which partisan excess on the left and the right endanger.

Hyperbolic indignation is an understandable reaction to some of the real or perceived excesses of the Trump administration, but it is poor counsel. The Trump administration views politics as a transactional process, which makes policy-making analogous to negotiating or leveraging business deals. However, there seems to be an insufficient appreciation of which measures are good for business and which ones are not.

In an insightful editorial, Michael Brodeur, a classical music critic for the Washington Post, has noted the slumps in ticket sales and attendance for both of the Kennedy Center’s premiere resident artistic institutions: the Washington National Opera and the National Symphony Orchestra. He observes that politicizing an arts center that depends on revenue is bad for business and no way to hold or attract audiences.

Analogously, one of the underexposed but important facts about the Fulbright Program is the enormously important role foreign governments in countries with binational Fulbright commissions play in cosponsoring and co-financing its bilateral exchanges. According to the official statistics available in the annual reports of the FFSB, foreign countries have contributed an average of over $100 million to the program annually since 2010. This money not only flows into the coffers of American institutions of higher education in the form of tuition and fees; it also funds the grant opportunities for thousands and thousands of American Fulbrighters from all over the United States to live and study abroad.

Foreign countries are hesitant to criticize the behavior of the Trump administration because they want to maintain the Fulbright Program and fear retaliation. However, rumor has it that some countries have reduced or are scaling back their contributions to the program, and others no doubt are thinking about it. This is bad for business, too.

In conclusion, the Fulbright Program and the Kennedy Center both would benefit if Congress would be more proactive in terms of its bipartisan responsibilities to oversee the non-partisan programs and institutions it has established by federal law and funds with annual federal appropriations.

The cultivation of institutional memory is also exceptionally important because it reminds us all of the larger underlying objectives that inspired the creation of these programs and institutions, and the upcoming commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the United States in 2026 coincides with the 80th anniversary of establishment of the Fulbright Program in 1946.

However, the Trump administration’s State Department also has shown little interest in historical memory and a genuine disinterest in its own history. It launched a new website on June 1, 2025, that entailed replacing the old internet domain of the Bureau for Educational and Cultural Affairs at https://eca.state.gov with a new one at www.state.gov/eca. The old ECA website provided an informative overview of ECA’s programs and initiatives whereas the new one merely links to an alphabetical table of contents. Furthermore, the old ECA subdomain on the Fulbright Program and its history disappeared altogether. Thank God these pages were archived by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine on May 31, 2025.

Lonnie R. Johnson, a native of Minnesota, has lived and worked in Vienna, Austria, in international education for over forty years and served as the executive director of the Austrian Fulbright Commission from 1997 until his retirement in 2019. The author of numerous books and articles on Central European history, his work in recent years has focused on the history of the Fulbright Program for a book with the working title Remembering and Forgetting Fulbright: The Remarkable History of the Fulbright Program from Truman to Trump, 1946-2026 (University of Arkansas Press). He has done research numerous times in the University of Arkansas Library’s special collections.

(Photo: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; donated in appreciation for his wise counsel by Senator Fulbright's partners at Hogan & Hartson. © Estate of Gretta Bader)