Here's how to trust online photos, really. By Alan Kotok

Much of the way we understand events is from the “pictures in our heads,” a term coined over a century ago by Walter Lippman. Those pictures formed in our brain cells are often the result of photos or videos we see in print, broadcast, or online media.And in some cases, those news photos can change the world. Retired public diplomacy officer James Nealon, in an essay posted Jan. 29 on his Substack, highlights news photography that galvanized public opinion, showing photos by Matthew Brady from the Civil War battle of Antietam, to the napalm girl in Vietnam, to Iraqis abused at the prison at Abu Ghraib.

Nealon goes on to say that today, “We no longer have to depend on a single photographer being in the right place at the right time to capture a moment and change the course of history. Now, of course, we’re all war correspondents with cellphones in hand.”

But having every mobile phone user become a news photographer or videographer raises serious questions about the reliability of those images, particularly after their capture. After all, we've had Photoshop making wholesale changes to digital images since 1987, and now with artificial intelligence you don't even need an original photo to create a realistic image portraying an event -- whether the image maker was at the event or if the event even happened.

The task of showing if news photos are real or fake has fallen on those of us who take or publish news photos, since our livelihoods depend on maintaining the trust of our audiences. But for many of us, representing reality in our photos is a responsibility we take seriously. So seriously, in fact, that the National Press Photographers Association code of ethics says, “Editing should maintain the integrity of the photographic images’ content and context. Do not manipulate images or add or alter sound in any way that can mislead viewers or misrepresent subjects.”

Fortunately, we’re helped by an industry project begun by Adobe, the software company that created Photoshop. About five years ago, Adobe joined with other software companies and publishers to form the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity or C2PA, “to develop an end-to-end, open standard for tracing the origin and evolution of digital content.” The group produced an industry specification called Content Credentials to identify a digital media product’s creator, as well as the steps it followed from start to finish.

With digital images, camera makers and media software companies add Content Credentials as extra data, called metadata, to the image file. These metadata identify the photographer and show the editing to produce the final image. Content Credentials are added to other standard metadata already collected in the image file, called Exif, short for Exchangeable Image File Format. Exif data show the date and time of creation, camera, lens, geographic location, and other technical and quality details.

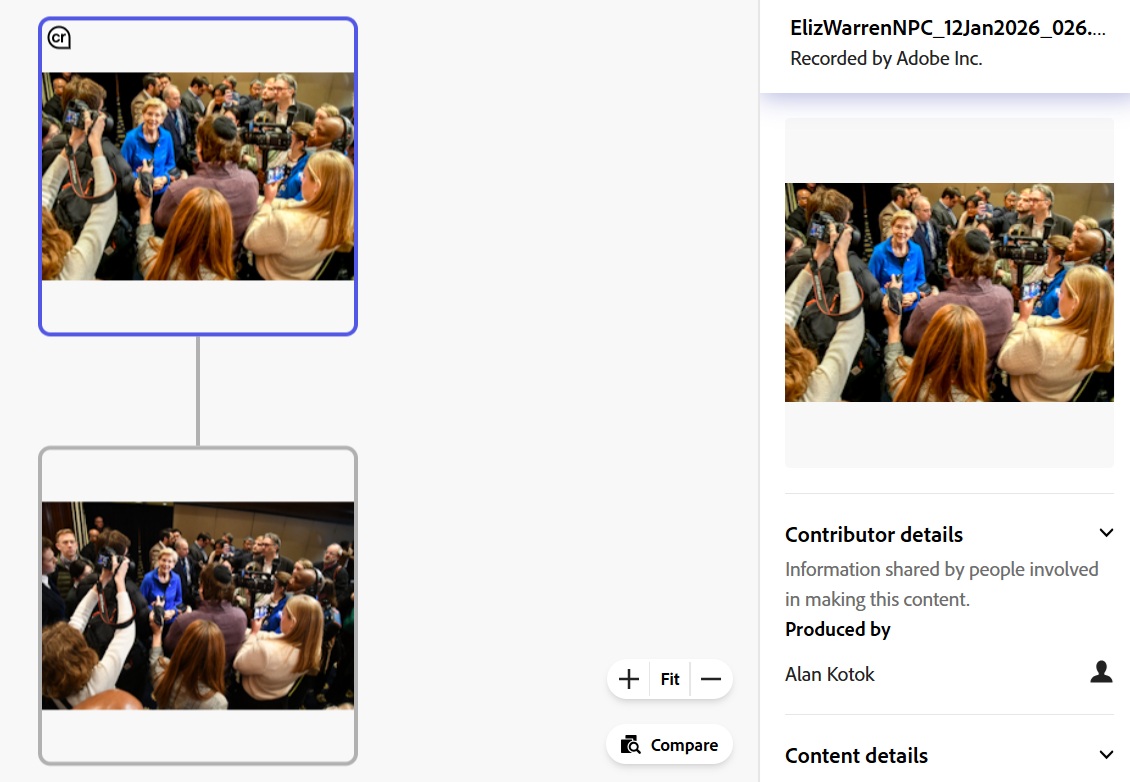

Content Credentials example

Here’s an example of Content Credentials with a real news photo in my company’s library, shot on Jan. 12 of Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) at the National Press Club answering questions from a gaggle of reporters. Click on the information icon (the letter “i” in a black circle) in the left-hand column to see the Exif metadata. I added Content Credentials to the image with Adobe Lightroom Classic photo editing software.

Adobe offers a page to inspect an image for Content Credentials. Here’s a screenshot of the Content Credentials inspection page for the Elizabeth Warren gaggle image. It shows the final edited image at the top and the original image as shot at the bottom. In the right-hand column is the first part of the Content Credentials with my name as the producer.

(Mobile users: Rotate your phone to horizontal/landscape orientation to view the images.)

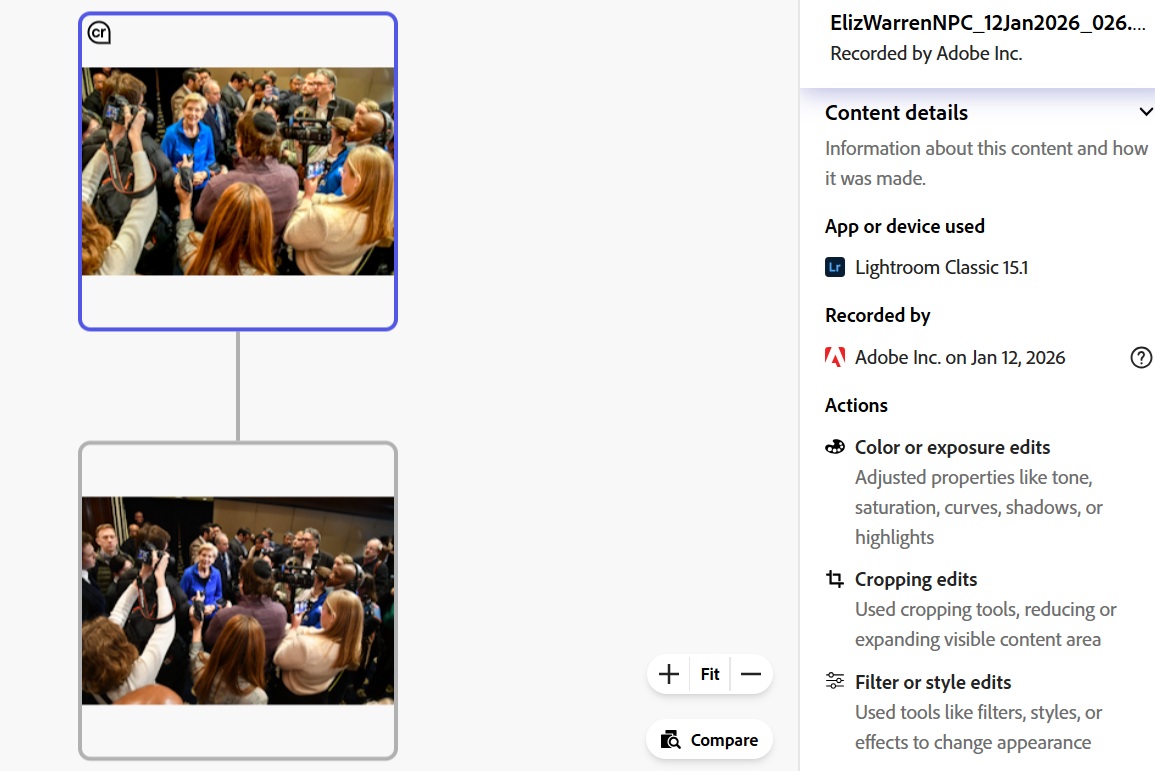

The following screenshot shows the rest of the Content Credentials in the right-hand column with the software used (Adobe Lightroom Classic) and the image edits. The page shows I cropped the image and enhanced the contrast with a preset provided by the software.

Online publishers are beginning to identify images with Content Credentials, displaying a small circular bug with the letters "Cr". Here's that photo posted on LinkedIn, a publisher that supports Content Credentials. Note the Cr bug in the upper left corner of the image.

Many digital camera companies such as Nikon, Sony, and Leica are adding Content Credentials to their native images. In addition to Adobe, other image software makers are expected to support Content Credentials in coming months. Note that Google, Microsoft, and Meta are on the C2PA steering committee.

If you're a strategic communicator or publisher, consider asking contributors to provide Content Credentials with their images, to protect yourself and build trust with your audiences. To paraphrase Ronald Reagan: verify first, then trust.

Alan Kotok is an ex-USIA journalist, photographer, and entrepreneur, now CEO of Technology News and Literature (technewslit.com) providing visual storytelling services to companies and organizations. He shoots news photos for the Alamy photo agency in London and serves as photography chair at the National Press Club.

- 30 -